By Christopher Vane M.A.

Chester Herald

College of Arms, London England

September 2019, a report from College of Arms: “There are entries for both John Rutledge ((1739-1800) and Edward Rutledge (1749-1800) in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Both were educated in England at the Middle Temple. There is also an entry in that work for an uncle of theirs, Andrew Rutledge (c.1709-1755). Of him it is stated: “[He] was descended from the Rutledges of Ireland, where it is believed his father owned and operated a farm in co. Cavan, in Ballymagied near Baronlog. The names of his parents and the exact location of [his] birth are unknown…”. But, an Andrew Rutledge “son and heir of Thomas R, late of Callan, County Kilkenny Ireland, esq, dec’d” was admitted to the Middle Temple on 1st February 1725/6. Thus the statement in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography looks unlikely to be correct.

Rutledge might well be a variant of the surname Routledge. Routledge is an English surname from the western end of the England-Scotland border, that is to say the county of Cumberland. There was a lot of emigration from this area to Ireland in the 17th century. Many Cumbrian surnames, such as Armstrong, Graham, Musgrave, Ponsonby, Blennerhasset and Briscoe found their way to Ireland at this time. An alternative possibility is that it is an anglicised version of an Irish name Mulderrig: see MacLysaght’s Irish Names page 307.

England and Ireland had different systems of heraldry and different heralds.

As a general rule today, in order to be entitled to arms, one must either be the person to whom the arms were granted or a direct descendant in a legitimate male line of (i) such a man or (ii) someone whom the heralds had accepted was entitled to arms. The reference to “someone whom the heralds had accepted was entitled to arms” in practice is to someone who was recorded as entitled to arms at one of the heraldic visitations, which the heralds conducted of individual counties between about 1550 and 1700. The visitations were designed to sort out who was and who was not entitled to arms. At the visitations, it was possible to establish that one was entitled to arms on the basis of long-open use by one’s ancestors. This is no longer the case. Two people with the same surname may have quite different arms while others with the same surname may not be entitled to arms at all.

At all times significant numbers of people have just assumed “arms” irregularly and without lawful authority. This may be a matter of regret to the heralds but it is a fact of life. The heralds have always had difficulty controlling the irregular use of arms. Such irregular use of arms is often of considerable historical interest.

If the Rutledges had arms, I suppose it is likely that they had either Irish arms by descent or English arms as original grantees.

I have looked through our indexes of English arms and found no references to anyone with the surname Rutledge having arms. There were few grants of arms to Americans in the 18th century, although I did find a grant to a Daniel Heyward of Granville County, South Carolina in 1768 where the petition was brought by his eldest son, Thomas Heyward of the Middle Temple. This Thomas Heyward was born in 1746 and so could have been at the Middle Temple at much the same time as John Rutledge: College of Arms – D14/49. I think that Thomas Heyward [also] signed the American Declaration of Independence.

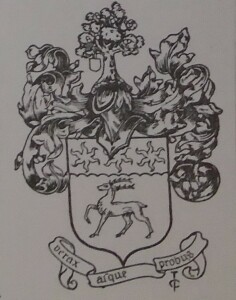

I have searched the Irish Records. I found records of two grants of arms to persons called Ruttledge (with two ts), but they both date from the first half of the 19th century and in any event the arms in question bear no resemblance to that in the illustration you sent me. I will send with this report a photograph of the entries for these families from Burke’s Irish Landed Gentry of 1912. As you can see the arms are quite different.

In a book entitled Burke’s Colonial Gentry (published 1894) there is an entry for a family settled in Australia called Rutledge. They were living at a place called Werrongurt in the state of Victoria. The first paragraph of the section of the entry headed “Lineage” runs as follows:-

“This family, of English origin, settled in Ireland in the time of Oliver Cromwell and owned the lands of Ballymagirl, near Bawnboy, co. Cavan, Ireland for several generations”.

This family were not credited with arms in that book. For what it is worth I suspect that Ballymagied (see paragraph 2 of this report) and Ballymagirl are one and the same place.

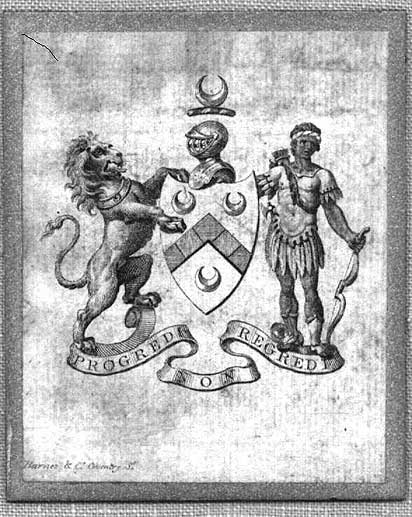

There is an entry under Rutledge in Bolton’s American Armory (published 1927). This work does not seek to distinguish between arms which have been lawfully granted and those which have just been self-assumed. The reference gives for Rutledge:-

Coat of Arms – Argent on a Chevron Azure between three Crescents two Lozenges Gules

Crest – A Crescent

The reference continues as follows:-

“Bookplate Edward Rutledge, signer of the Decl. of Indep. and used as temporary seal of So. Car. by John Rutledge, pres. of the independent gov. set up 1776. The drawing is: Argent a Chevron compony Azure and Gules between three Crescents.”.

This last description fits the coat of arms in the illustration which you have sent me.

Further, in heraldry, different people have rather different helmets. The helmet in the illustration has bars: a commoner is not entitled to this sort of helmet.

My conclusion therefore is that the Rutledge family just adopted the arms in the illustration informally and without the authority of the College of Arms. This sort of thing happened a lot.

People not infrequently ask the meaning or symbolism of particular colours, shapes or charges in heraldry. It is sometimes obvious why a particular family has a particular charge in its arms. For example, punning is not rare in heraldry and it is not difficult to see why someone with the surname Bull might have a bull in their arms. Lions frequently appear in heraldry: I suppose they can be said to represent strength, vigour and that sort of thing. My guess is that the figure on the right is meant to be a Native American. But I do not think one can say generally that a particular colour or design has a particular meaning or significance. I do not think there is any particular significance in a chevron as against, say, a fess: they both represent convenient ways of dividing up a shield. Crescents are widespread in heraldry and I do not consider that they should be regarded as having any particular meaning.”

Motto – Progredi non regredi [To go forward not backward; proceed/progress not recede/regress]

On the left-hand side (from the point of view of someone standing in front of the shield) of the coat of arms in the illustration, there is a lion and on the right a human figure. In heraldry, these are called supporters. A commoner (i.e. a man without a title) would not have supporters